29 Nov 2021 09:00

Mapping Twitter conversations during the Referendum

In 1983, Ireland held its first referendum on abortion laws. Sparked by the landmark Roe vs. Wade case in the U.S. Supreme Court – granting women the freedom to receive an abortion – the pro-life campaign wanted to ratify the existing ban on abortion and prevent its potential legalisation in Ireland. The motion passed with a 67% majority (O’Carroll, 2013). Over three decades later, in 2018, Ireland voted to legalize abortion with a second referendum, which passed with 66.4% of the vote (Henley, 2018). This resounding change in attitudes coincided with the growth of an increasingly liberal attitude towards abortion laws globally (Vogelstein, 2019) and a locally declining influence of the Catholic Church on private life in Ireland (Drążkiewicz et al., 2020). However, despite legal changes in favour of liberalisation (World’s Abortion Laws Map Progress, 2019), there are groups still that passionately resist this change, both in Ireland (Wilson, 2021) and globally (Brenan, 2021), making the issue a highly polarising and contentious one. While the 2018 referendum was described as “respectful” compared to the “divisive and nasty” vote in 1983 (McGee, 2018), it is important to account for the shift to digital mediums for confrontational rhetoric today, which may have been just as divisive and, as this article aims to show, fosters a breeding ground for misinformation.

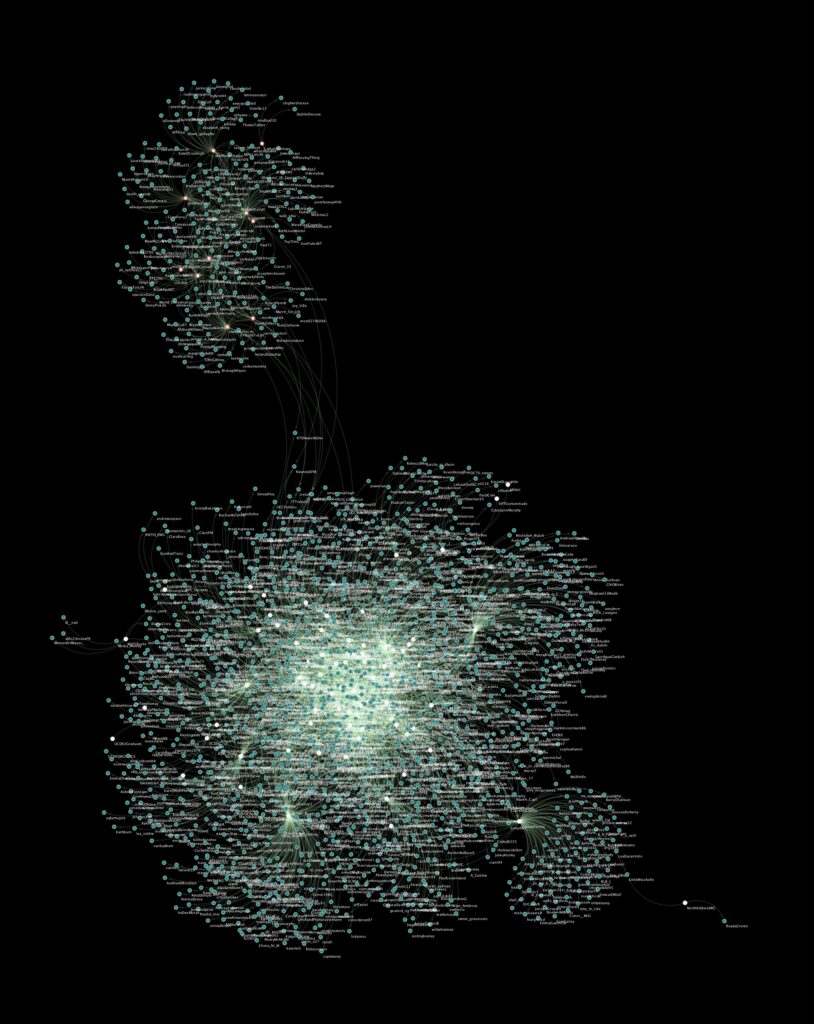

To investigate the digital narrative surrounding the referendum, I chose to analyse Twitter data in the month leading up to and during the 2018 abortion referendum. Using over two million Twitter posts, I hypothesised that the main ingredients for a viral (highly retweeted) post would a) express a positive, rather than negative sentiment and b) be classified as being from official news or campaign handles. I further hypothesised that there would be little engagement between the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ campaigns online i.e., the debate would be quite polarised. While I found that campaigns showed little cross reposting (see image below), contrary to my hypotheses, negative sentiment and content shared by individuals – rather than news / campaign accounts – showed a significant and positive relationship with reposting.

Network Analysis of the tweets. The smaller cluster on top tweets endorsing the no-campaign. Lines represent re-tweets, dots represent accounts. White dots represent official sources (defined as local Irish political parties, news accounts, campaign accounts).

Network Analysis of the tweets. The smaller cluster on top tweets endorsing the no-campaign. Lines represent re-tweets, dots represent accounts. White dots represent official sources (defined as local Irish political parties, news accounts, campaign accounts).

Taken together, these findings suggest the messaging which received the most attention was highly negative and emotive content, shared by individuals. Indeed, the account with the highest number of retweets was an individual with 983 followers. This pales in comparison to RTE News’ 697,775 followers, the most followed Irish-based Twitter account in the dataset and the national broadcaster in Ireland. This is in line with recent descriptions by social anthropologists who describe the referendum as “one example of dramatic social change driven by grassroots activism” (Drążkiewicz et al., 2020, p.562). The tweet (original linked below) contains a pledge to repeal the 8th amendment – which was put into place in 1983 – drawing on the case of Savita Halappanavar, a 31-year-old woman who died of sepsis in 2012 (BBC News, 2012) due to being denied an abortion. Savita was widely cited throughout the referendum and “became something of a martyr for abortion rights” (Drążkiewicz et al., 2020, p.564).

The second most shared tweet, receiving 5000 reposts, featured another popular hashtag of ‘home to vote’, due to the number of Irish expats travelling back home to cast their vote. However, Savita Halappanavar clearly emerged as the top theme with the ‘Yes’ campaign as this tweet received over 18,000 reposts. The disparity between the most and second-most retweeted tweets is an important feature as it indicates that the relationship between negative sentiment and viral posts may be driven by the mention of (Savita’s) death. Wider research looking at the relationship between emotive content and sharing has in fact shown that it is a driver of post-sharing and virality (Berger & Milkman, 2012).

Taken in isolation, it might seem unsurprising and perhaps harmless that highly emotional content goes viral. However, research looking into the rise of misinformation online finds that factually incorrect or misrepresented content tends to be strongly evocative, amongst other features (Acerbi, 2019; Brady et al., 2017). Though an emotional post does not imply that it contains misinformation, this is a concerning finding when paired with the lack of news or even official campaign reposting during the referendum on Twitter. Additional analysis of the network of reposting (displayed visually above) also found support for the presence of polarised clusters by campaign, which can exacerbate the problem of misinformation (del Vicario et al., 2016).

Social media and Internet companies were keenly aware of these dangers of as Facebook blocked political advertisement outside Ireland and Google blocked all referendum-related adverts. Many interpreted this as an experimental policy following the rampant criticism of politically divisive ads during the 2016 American presidential election (Satariano, 2018). Twitter did not take any additional action pertaining to the referendum (Dasgupta et al., 2018). Bots are another well-documented method for spreading misinformation (Himelein-Wachowiak et al., 2021). While the current analysis excluded 1257 potentially spam/ bot tweets, a similar analysis of Twitter data during the referendum found about 4% of the dataset were likely to be bots (Dasgupta et al., 2018).

Nonetheless, the Irish abortion referendum was one of the few encouraging cases in recent years as neither my social media analysis nor Dasgupta et al. (2018) found explicit evidence of misinformation on Twitter. On a global stage, commentators applauded the 2018 referendum as an exemplary democratic process as the Irish government used a “citizens’ assembly”, a group of 99 randomly chosen citizens to represent the views of Ireland prior to announcing the vote (McGreevy, 2018). Others also noted the effective use of “brute statistics” by the ‘Yes’ campaign (Drążkiewicz et al., 2020), in contrast to the findings about emotion above. However, although the debate seemed insulated from misinformation, it could be a contextual feature as others have found evidence of misinformation, foreign interference, and bots during the campaigning stages, but conclude that they had little to no impact on voters or the outcome (Lavin & Adorjani, 2018). Still, as is the case with a significant proportion of misinformation today, there could have been unobserved fake news spreading on private messaging applications such as WhatsApp (Rivero, 2021).

References

Acerbi, A. (2019). Cognitive attraction and online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0224-y

BBC News. (2012, November 14). Woman dies after abortion request “refused” at Galway hospital.https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-20321741

Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What Makes Online Content Viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0353

Brady, W. J., Wills, J. A., Jost, J. T., Tucker, J. A., & van Bavel, J. J. (2017). Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(28), 7313–7318. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1618923114

Brenan, B. M. (2021, August 13). Record-High 47% in U.S. Think Abortion Is Morally Acceptable. Gallup.Com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/350756/record-high-think-abortion-morally-acceptable.aspx

Dasgupta, A., Kaminska, M., Metaxas, P. “., Dasgupta, A., Kaminska, M., Metaxas, P. “., Macaj, G., Ansell, B., Ennis, P., & Arcarons, A. F. (2018, September 24). Tracking the Twitter conversation on the Irish abortion referendum. OxPol. https://blog.politics.ox.ac.uk/tracking-the-twitter-conversation-on-the-irish-abortion-referendum/

del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., Stanley, H. E., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517441113

Drążkiewicz, E., Strong, T., Scheper‐Hughes, N., Turpin, H., Saris, A. J., Mishtal, J., Wulff, H., French, B., Garvey, P., Miller, D., Murphy, F., Maguire, L., & Mhórdha, M. N. (2020). Repealing Ireland’s Eighth Amendment: abortion rights and democracy today. Social Anthropology, 28(3), 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12914

Henley, J. (2018, May 26). Irish abortion referendum: yes wins with 66.4% – as it happened. Guardian. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2018/may/26/irish-abortion-referendum-result-count-begins-live

Himelein-Wachowiak, M., Giorgi, S., Devoto, A., Rahman, M., Ungar, L., Schwartz, H. A., Epstein, D. H., Leggio, L., & Curtis, B. (2021). Bots and misinformation spread on social media: A mixed scoping review with implications for COVID-19 (Preprint). Journal of Medical Internet Research. Published. https://doi.org/10.2196/26933

Lavin, R., & Adorjani, R. (2018, June 1). How Ireland Beat Dark Ads. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/01/abortion-referendum-how-ireland-resisted-bad-behaviour-online/

McGee, H. (2018, May 27). How the Yes and No sides won and lost the abortion referendum. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/how-the-yes-and-no-sides-won-and-lost-the-abortion-referendum-1.3509924

McGreevy, R. (2018, June 21). Citizens’ Assembly is an example to the world, says chairwoman. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/citizens-assembly-is-an-example-to-the-world-says-chairwoman-1.3539370

O’Carroll, S. (2013, December 27). History lesson: What happened during the 1983 abortion referendum? TheJournal.Ie. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.thejournal.ie/abortion-referendum-1983-what-happened-1225430-Dec2013/

Rivero, N. (2021, March 3). Can WhatsApp stop misinformation without compromising encryption? Quartz. https://qz.com/1978077/can-whatsapp-stop-misinformation-without-compromising-encryption/

Satariano, A. (2018, May 25). Ireland’s Abortion Referendum Becomes a Test for Facebook and Google. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/25/technology/ireland-abortion-vote-facebook-google.html?smtyp=cur&smid=tw-nytimes

Vogelstein, R. B. (2019, October 28). Abortion Law: Global Comparisons. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.cfr.org/article/abortion-law-global-comparisons

Wilson, J. (2021, October 14). Anti-abortion group launches billboard campaign ahead of three-year review. The Irish Times. Retrieved October 20, 2021, from https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/anti-abortion-group-launches-billboard-campaign-ahead-of-three-year-review-1.4700499

World’s Abortion Laws Map Progress. (2019, May 28). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__IeifPzqh8&list=TLGGymBKepxRP_IyMDEwMjAyMQ

Trisha is a Research Assistant at the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab where she works to understand, measure, and counter misinformation pertaining to vaccine hesitancy. Prior to this role, she completed her MSc in Behavioural and Economic Science and BA (Hons) in Philosophy Politics and Economics at the University of Warwick.

Trisha’s MSc dissertation looked at a large volume of tweets around the Irish Abortion referendum, using text analysis to understand the drivers of reposting tweets. As an aspiring doctoral student, she aims to conduct research on timely social and political issues such as misinformation, from a cross-cultural lens to inform public policy and behavioural interventions.