Beulah Ezeugo: Archiving Marginalised Communities

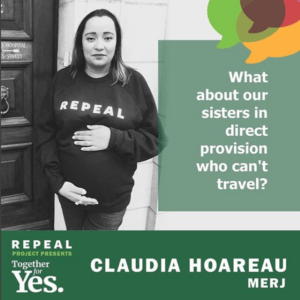

Migrants and Ethnic Minorities for Reproductive Justice (MERJ) members Beulah Ezeugo and Emily Waszak got together to talk about what Archiving the 8th means for marginalised communities whose work is often overlooked or purposefully excluded from hegemonic narratives.

They deliberately and intentionally chose an interview style over more static academic writing to highlight the importance of oral histories and the accessibility of language and format. Who is the audience? Don’t our communities have just as much right to access this as any academic studying the 8th?

Beulah: How would you like to start?

Emily: Maybe we could start with some questions. First, why we’re here talking about archiving the 8th. Or like why is it important specifically to us as MERJ members to think about how the campaign to repeal the 8th amendment will be recorded and preserved.

Beulah: I’ve been looking at the pictures you shared, it seems so long ago! What struck me is how many gaps there were to be filled. I’m thinking specifically about the infographic with guidelines for people without citizenship who wanted to participate, the posters in solidarity with Argentina… I think that archiving the repeal campaign is important to me because it represents a specific time where all of the invisible work that we do was so evident. I’m not sure if that makes sense.

Emily: Yes! I was struck by the same. I think I have blocked a lot of that out because it was so intense and, to be honest really painful to be not only fighting against the NO side with their really horrific attacks, but also to be fighting for our right to be heard, and really just exist as ourselves, within Together for Yes (TFY) and the whole Repeal the 8th campaign more broadly. But that was our work. It has always been our work and the work that is always left to the most marginalised–to, as you say, fill the gaps and amplify the hidden voices and the hidden work. We were speaking to the people like us– migrants, people of colour (POC), Travellers, trans and non-binary people–the people who the mainstream repeal campaign made a conscious decision to ignore and exclude.

Emily: Yes! I was struck by the same. I think I have blocked a lot of that out because it was so intense and, to be honest really painful to be not only fighting against the NO side with their really horrific attacks, but also to be fighting for our right to be heard, and really just exist as ourselves, within Together for Yes (TFY) and the whole Repeal the 8th campaign more broadly. But that was our work. It has always been our work and the work that is always left to the most marginalised–to, as you say, fill the gaps and amplify the hidden voices and the hidden work. We were speaking to the people like us– migrants, people of colour (POC), Travellers, trans and non-binary people–the people who the mainstream repeal campaign made a conscious decision to ignore and exclude.

Beulah: Exactly. In retrospect, it’s very clear that TFY was a campaign that sought to center a certain type of reproductive injustice that affected only one type of person, specifically white settled Irish cis-women. I feel like this became so much more insidious when it was coupled with a tokenization of some POC experiences while ignoring others. But yes, it’s also really important to acknowledge that – not only do you have to live out the violence during the campaign, you’re also forced to relive it during the process of recording it. You spoke a little about some of your correspondences afterwards and how a lot of what MERJ members and migrants in general experienced pre-repeal and during the campaign was dismissed or even denied.

Emily: Oh yes for sure. During the campaign we were always seen as an afterthought or some kind of niche issue, when the reality was that migrants and ethnic minorities were disproportionately affected by the 8th amendment, so best placed to be speaking about it and organising against it. And we know what happened and we remember who said what. But in hindsight after Repeal, some people wanted to just celebrate and move on. Some people did not want to remember the ugliness that they participated in, just the hero narrative that they brought abortion to Ireland in the end.

But for some of us, particularly the people who still aren’t able to access abortion in Ireland, and the people who were excluded, we still remember and are still looking for acknowledgement and accountability (if not an apology), because if we forget what happened, how some communities were seen as expendable so that some middle class white settled Irish people could get abortions, then we will just continue to perpetuate the cycle of exclusion. There is a direct line from the exclusion of women of colour by the white suffragettes to TFY with no learning in the hundred years in between.

Beulah: Very true.

Beulah: Very true.

Emily: This also brings up the idea of contested narratives and disputed memory. When after the campaign people who were excluded spoke out, the people who participated in the exclusion either pretended not to hear, became defensive, or in some cases, as you said, denied any exclusion or knowledge of it. It is a kind of cultural gaslighting that becomes institutionalised when the dominant narrative is the only narrative that is archived or remembered. So how do we make sure that these contested narratives are preserved?

Beulah: I’m weary of invitations to “correct the record” by the same people who did the gaslighting and dismissal in the first place. Often that means being invited into these formalised record keeping systems – who legitimate those systems in the first place.

I don’t think it is an act of justice or redemption to invite us to participate or build around the frameworks that excluded us in the first place. I think that the best option is to co-create our own records. I guess that brings me to ask, if we (MERJ) want to do our own memory work re archiving the 8th, where do we start?

Emily: This is a question we’ve asked ourselves so many times. We have started a collective timeline and one that has space for people to contest or remember differently. We have collected ephemera, but mostly digital, as we have no actual collective physical space. And that is about it. Mostly because we don’t have resources, capacity, etc. We have talked about a book but we are always busy working on urgent campaigns, so the archival work always gets put off. It would be great to collect some oral histories as well. But this is always the tension–if we don’t trust the main archival institutions, but we also have no resources to archive it ourselves, there is the danger that it just gets lost to our memories. There is also the question of gaze. Who do we want to see in the archive? If it’s for ourselves, then grand, DIY all the way. But if it’s for people beyond us it seems like we need a strategic plan for it. What is your vision for the archiving of our work and memory?

Beulah: Yeah it is a labour of love but a lot of labour nonetheless. Especially if you don’t have the physical resources, the emotional capacity, and in some cases the qualifications. That sounds a lot like what Gabriel Soils calls endangered knowledge – when counter-narratives are in danger of being suppressed because of the structural barriers that prevent people from sharing, or emotionally harm them so much that they cannot share at all.

I’m a very big proponent of the DIY option – obviously. There is also a lot of space to imagine what an informal record keeping system for MERJ may look like and what cultural frameworks it may take on. It doesn’t necessarily have to exist as a sanitised index of material. Like you said, oral histories are so important, and a story that is constantly retold is just as valuable as a document or written.

I also believe that community archives are valuable, especially those that are collectively formed by the people who really experienced the event(s) they are documenting. Since creating Éireann and I, Joselle and I have done a lot of thinking about the value of using more intentional language when talking about the archive we’ve formed. Even though it is a community archive, the material in it is the outcome of individuals’ experiences with multiple states and global communities. I guess I don’t really have an answer re. gaze but I think these two things are connected. Perhaps the strategy can simply be doing what we can but also doing it with intention and honesty, i.e naming things exactly as we see them and locating them precisely within greater structural issues. I think that would prepare us for whatever future audience might find and seek to understand whatever we’ve left behind.

I also believe that community archives are valuable, especially those that are collectively formed by the people who really experienced the event(s) they are documenting. Since creating Éireann and I, Joselle and I have done a lot of thinking about the value of using more intentional language when talking about the archive we’ve formed. Even though it is a community archive, the material in it is the outcome of individuals’ experiences with multiple states and global communities. I guess I don’t really have an answer re. gaze but I think these two things are connected. Perhaps the strategy can simply be doing what we can but also doing it with intention and honesty, i.e naming things exactly as we see them and locating them precisely within greater structural issues. I think that would prepare us for whatever future audience might find and seek to understand whatever we’ve left behind.

Emily: That’s a really great way to think about approaching memory work. There’s so much there to examine and try and as always I’m really excited and grateful to get to work on this with you and everyone in MERJ!

Beulah: Me too! Thank you for your wonderful insight, as always.

Published: 1 September 2021

Beulah Ezeugo is an Igbo artist, curator, and researcher currently based in Glasgow. Her work centres Black postcolonial dreaming using collective memory and myth. Her practice is informed by a social science background from University College Dublin and an MLitt in Curatorial Practice from Glasgow School of Art and the University of Glasgow.