Recording Oral Histories

If you are engaged in an Oral History project, first ask yourself if it is legal and ethical. It is vital that your interviewee is aware, from the beginning, about the purpose of the project, what participation means, and how their interview will be used.

Ensure you have recording equipment such as an audio recorder or dictaphone and that you feel comfortable using it to create .wav files. Remember – most mobile phones also have this facility!

Back up your interviews – store them online and on a memory bank or USB stick.

Unlike other historical records your interviewees, and the people they refer to during their interviews, are people with legal rights and protections. Copyright must be transferred to you / your project / the archive you select before you can use the recordings for any purpose. Data protection legislation dictates what information you can store about another person and how that should be stored; ethical decisions must be taken when dealing with vulnerable interviewees or sensitive and/or confidential information.

Key points to note are:

Do you need ethical approval?

Does the interviewee understand how you will use their recordings?

Are you open to anonymising participants?

Should access to your interview be sealed off for a period of time?

You must provide an information sheet about the project and ensure that the interviewee understand what is involved. It is unethical and in some cases illegal to use interviews without the informed consent of the interviewee. The Oral History Network of Ireland have created a sample pack to help with this. Always remember the principle of ‘do no harm’ and ensure that you conduct the interview material in an legal and ethically sound manner.

Creating Your Own Consent Forms

When recording your oral history interviewee, always prioritise your safety by ensuring that everyone involved is happy with the interview arrangements. Conduct your interviews in a safe and private environment such as a women’s or community centre, or a participant’s home. Remember, interviews in locations such as coffee shops may be impacted by background noise.

Ensure that you bring questions you would like to pose with you proper to the interview. This will help structure your interview and get the most out of your session.

Always remember that oral history interviews are about interviewing people who lived through important historical experiences. Be mindful of triggering subjects and conduct your work with empathy. If possible, bringing a list of relevant support services to give to participants at the end of the interview may be helpful.

It is good practice to give a copy of the interview to participants involved and to check in with them before publishing any of their accounts. This will create trust and provide clarity to your interviewee.

A good consent form will tell interviewees:

The purpose of the interview/s

The funding source (if any)

Your contact details

What is involved in participation

Will outline any benefits/risks to participation

Ensure that interviewees understand they are under no obligation whatsoever to take part in the interview/s and may leave at any time without explanation

A consent form should also offer confidentiality.

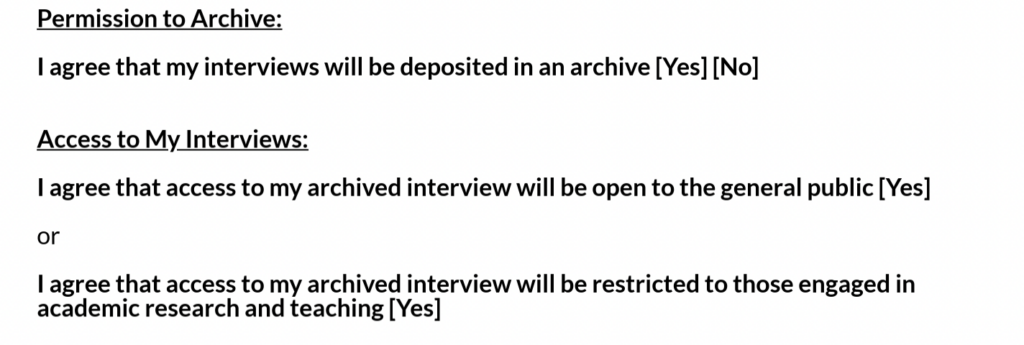

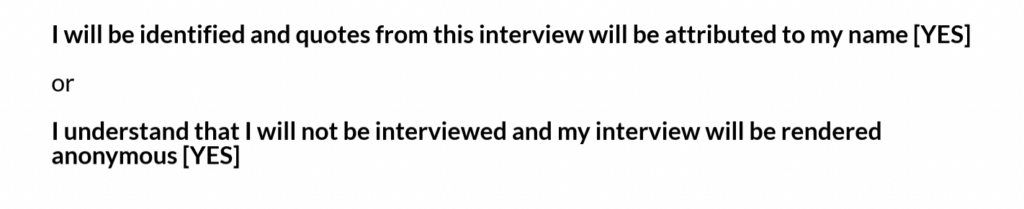

Here are some examples of how to phrase confidentiality questions:

The consent form should also explain how the data will be used and it will outline how long it will be retained for. If you wish to archive the data, you need to ask permission to archive the data and explain who will have access to it.