22 Nov 2021 09:00

#Repealthe8th: Online Activism’s Impact on the Referendum

In the week leading up to the Repeal vote, a video appears on my Twitter feed, hashtagged with #HomeToVote. The sight of Dublin Airport filled with activists carrying signs, wearing black REPEAL jumpers, and welcoming expats home is deeply moving. I wipe away a few tears before I hit retweet. Later, I discuss it with fellow activists: “Have you seen all the Home To Vote posts?” “I’m in bits, I can’t stop sobbing.” We’re aware that Tweets can’t promise victory and that our feeds are bound by algorithms and feedback loops that create political echo chambers. Trusting social media means trusting platforms that promote content designed to encourage us to keep clicking. Yet, even knowing this, we’re unable to deny that something is happening, a pull we are all feeling: this hashtag has given us hope.

Moments like these formed an anchor for my research into Repeal’s online activism. In examining online protest’s significance and relationship to grassroots campaigning on the streets, I was drawn to dialogues of hope, anger, and mourning felt in tandem across both spaces. Envisioning online and offline worlds as held together by what Williams’ “structure of feeling”, affective analysis offered a way to comprehend the ephemeral and messy charges of emotion, culture, and history that intertwined to make social media a valuable site of protest. Political debates over abortion have always relied heavily on emotionally charged statements and stirring imagery, a battleground in which anti-abortion campaigners have traditionally held the upper hand. Taking charge of this arena was a major challenge for activists—affective analysis helps parse how they achieved this organically, utilising social media to challenge narratives and bolster solidarity.

Online activism supported offline campaigning in two major ways: firstly, by offering strategies of digital protest including hashtags, profile pictures, and memes, and secondly, by providing unique spaces of resistance via its potential for anonymity and connection with wider audiences. Social media protest offers an opportunity to subvert typically individualised forms of expression—sharing personal stories and media—in order to form virtual crowds that instill a sense of collectivity by drowning out oppositional voices and flooding feeds. This was particularly relevant in the case of #Repealthe8th, which was the number one trending hashtag in the Republic of Ireland in 2018. Posting, retweeting, and sharing built an affective and political network that functioned in both an informative (‘this is what’s happening right now’) and community-focused (‘this is the outrange we feel, do you feel it too?’) sense. Reiterating support for Irish women and pregnant people in the digital sphere became another way to hold the government accountable for silencing them and to disrupt long held anti-choice myths about Irish identity.

Perhaps the most notable success of online campaigning was its ability to reclaim the visual terrain of the abortion debate, shifting it away from stereotypical (and often jarring) medical imagery of foetuses and toward representations of feminist solidarity. Somehow, amidst an emotionally taxing referendum campaign, activists were able to find brief interludes of laughter through memes poking fun at their love of badges and stickers and highlighting the hypocrisy of arguments from the ‘No’ side.

@iresimpsonsfans spreading the joy of activist badges: https://twitter.com/iresimpsonsfans/status/996856789948862469.

@iresimpsonsfans spreading the joy of activist badges: https://twitter.com/iresimpsonsfans/status/996856789948862469.

A meme turning one of the ‘No’ campaign’s poster’s on its head: https://twitter.com/ailbhes/status/989112231450304513.

A meme turning one of the ‘No’ campaign’s poster’s on its head: https://twitter.com/ailbhes/status/989112231450304513.

Profile pictures featuring supportive banners and frames, and selfies of people wearing the famous black jumpers solidified and amplified the sense of a collective “we”. The specific lettering of the jumpers became so prominent and easily recognisable that a Facebook filter was created for those who did not own a physical jumper, allowing them to virtually ‘put one on’.

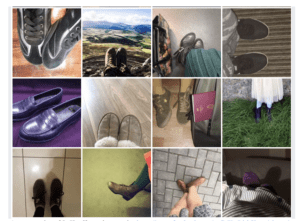

A particularly poignant example of visual resistance arose on the In Her Shoes project’s Facebook page, wherein anonymous stories of life under the Eighth were shared alongside pictures of authors’ shoes. The images draw individuals back into the narrative, not as carriers or wombs, but as people in their own right. They shift the visual focus back to the pregnant person and, in turn, to the collective survivors of reproductive violence. To encourage “walking in their shoes” opens potential for empathetic, unsettling responses as readers are asked to comprehend the weight of reproductive harm. The choice to show only the shoes isn’t just an anonymity measure, but a symbolic statement: as everyday items they serve as a reminder of how state abuse and medical neglect have been folded into the fabric of Irish life.

A cross-section of In Her Shoes photographs: https://www.facebook.com/pg/InHerIrishShoes/photos/.

A cross-section of In Her Shoes photographs: https://www.facebook.com/pg/InHerIrishShoes/photos/.

The networked space can memorialise marginalised histories in unique ways. One notable example of this phenomenon was the online memorialisation of Savita Halappanavar, who died in 2012 after being denied a potentially life-saving abortion. Her physical memorial site was visited by activists immediately following the referendum result, and images quickly circulated online so that the vigil could be attended virtually. Complex feelings of pain and relief—gratitude for a potentially brighter future, but an insistence upon continuing to mourn those lost—were shared across the country and the global Irish diaspora. Virtual memorialisation resists temporal and geographical boundaries. What exists stays (theoretically) forever, accessible from anywhere, resisting attempts to suppress the past. In this way, Repeal activists mobilised the porous boundary between offline and online spaces as a means to remember history and vow to keep fighting for a just future.

Discussions within digital spaces held tightly to the materiality of bodies and embodied, affective experiences. Digital culture allows for connections across time and space where personal, subjective bodily realities are articulated and related to in new ways, in what Baer calls a “re-doing” of feminism. Throughout my research, I witnessed this time and time again as people wrote about their own abortions on different platforms, recalling the terror of unwanted and non-viable pregnancies, the physical toll of overseas travel, anxiety about procuring abortion pills, and waves of both relief and shame. What I found particularly striking was not just these posts’ confessional nature, but the ways in which their affective dimensions were redirected back towards the Irish state. They frequently transformed the narrative from individual stories of trauma into shared histories of national oppression that Ireland itself should feel shameful for. Personal anger became collective in the hands of those affected by reproductive violence.

This focus on collective, feminist expressions of national identity forms the final key finding of my research, a theme that was most potently expressed through #HomeToVote. In Tweets recording Irish expats’ journeys home, Irishness featured in both whimsical—tweets promising Tayto crisps and calling those travelling home “absolute legends”— and deeply meaningful ways. With abortion itself having been banished from the physical land of Ireland, and women having been forced to travel outside its borders for decades, #HomeToVote as used in the context of abortion reform captured the symbolic, emotive power of Irish citizens taking the inverted journey to change the law. The word “home” functions on a deep affective level, drawing associations with family and nation used by the state to push its pro-natalist rhetoric and turning them on their head, locating home as a place of potential change that might finally become welcoming to those previously forced outside its social and physical borders.

For Ireland, a country fundamentally shaped by emigration, images of its citizens returning in order to cast their vote was endowed with a double layer of symbolism. That the same hashtag had aided in the legalisation of same-sex marriage three years prior made the moment all the more poignant; it signalled an alignment and overlap with LGBTQ+ activism and a deep commitment to broader grassroots social change. Irishness and Ireland as “home” became redefined and reclaimed through feminist discourse.

What might seem like trivial, fleeting interactions were utilised in strategic political ways to create affective communities. Understanding these engagements as part of a much broader matrix of online identity and feminist adaptation enables us to reframe them as everyday politicised acts that are formative to shaping the worlds we inhabit, both online and offline. Online activism wasn’t just important because of numbers, trending hashtags, and timelines overflowing with support. It wasn’t just the volume of this digital crowd, but the feelings and affective connections felt by each and every person who participated. There was a sense that even if we weren’t in that waiting room or couldn’t make it to that rally, we could still touch and be touched through our screens.

Niamh White recently graduated with an MA in Gender, Feminist, and Women’s Studies from York University, Toronto. Her masters research focused on digital protest and online feminist communities in the context of Irish and Northern Irish reproductive justice activism. Her upcoming PhD research at Monash University will build upon her interests in affect theory and digital spaces to investigate how young queer women use social media to engage with and shape queer history. You can contact Niamh via Twitter.